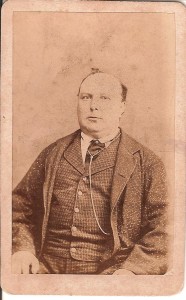

| PAUL VICTOROVITCH LIGDA | Born: 1872-09-01 | Died: 1932-08-06 | |

| Father: VICTOR NICHOLAS LIGDA | Mother: EMILIE CRAMER | ||

| Children: THEODORE PAUL LIGDA, MYRON GEORGE HERBERT LIGDA, MARY BARBARA LIGDA, VICTOR WORTHINGTON LIGDA | |||

| Siblings: VALENTINA LIGDA, MARY LIGDA, ELIZABETH LIGDA, SIMEON LIGDA, ALEXANDER LIGDA, PIERRE LIGDA , OLGA VICTOROVNA LIGDA, VLADIMIR LIGDA | |||

Paul was the third child to survive childhood born to Victor and Emilie. He was two when his family moved to Italy and seven when they moved to France. Paul did not attend school in France. Instead he was apprenticed, at age 12, to Jules Benarre, a cabinet maker with a small shop in Paris. Paul enjoyed carpentry and became quite skilled and established by the time he was 16. In 1889, as his family prepared to leave France for the United States, Paul, like his older sister, Olga, planned to remain in Paris. He changed his mind at the last minute, perhaps because Olga changed her mind and perhaps because he felt a special responsibility to his parents as their oldest son.

His family first settled in San Francisco where Paul found work in various places as a house carpenter, a cabinet maker, and a mill worker. 1 He lived with his family while he learned English. On July 25, 1894, he registered to become a naturalized citizen.

In 1895, Paul moved with his family to Oakland. He continued supporting himself and contributing to the family by work as a carpenter. 2 He completed the naturalization process on August 4, 1898 before the Hon. Charles W. Slack; and had his naturalization registered in Alameda County on August 10, 1907. 3

In 1900 Paul’s younger brother, Vladimir, graduated from high school with plans to enroll in college. Paul decided he wanted to go to college too. With no formal education, he had to take special entrance examinations covering an entire high school course. To prepare for those examinations, with Vladimir’s help, he studied for six months; and then, in two weeks, took the exams and passed with grades of 1 and 2 (1 being highly credible; 2 being pass). The brothers (27 year old Paul and 18 year old Vladimir) entered the University of California, Berkeley together.

Both continued living at home. Paul was an excellent student. His best grades were in mathematics and French. His weakest grades were in drawing. He did considerable tutoring in mathematics and physics. As an older student, he was remembered in other ways. The 1908 Blue & Gold contained this recollection:

“ . . . there we re two brothers in college. One Ligda was a track man; the other was simply a Russian. At one of our field days, Victor Ligda was a close second near the finish of a race. Brother Paul jumped up on the bleachers and called: “Run Victor, run. Maybe he will fall down and den you will beat him.” From that day on, Ligda was known about North Hall as Abodie ’04, or any of the other men who really made records.”

While in college, both Victor and Paul were active in theater. There is a picture of each of them in their costumes for performances of “The Student Prince.”

During his college years, Paul met and courted Pauline Hulse, who was to sue him for breach of promise when the relationship ended. Her suit was the subject of a poem in the 1905 Blue & Gold indicating that Paul lost that suit, but a newspaper account indicated otherwise.

In March of 1904, Paul met Edith Griswold, a second year student at the University who was living next door to the Ligdas at 673 33rd Street. Edith made a note of their going out on April 8. Over the remainder of the school year, they rode to and from school together on the street car. Paul also tutored her in mathematics.

Paul graduated from the University on May 17, 1904 and celebrated with an all night party (which Edith reported to her diary). Edith left shortly thereafter to spend the summer with relatives in Walla Walla, Washington. They began a remarkable correspondence: 4

***

5/21/04- Dear Miss Griswold:

I am missingyou sadly . . . I climbed up Grizzly peak Wednesday . . . alone. Isat down for a couple of hours. What will the future bring me?

Yoursferociously, Paul Ligda

***

5/28/04- Dear Mr. Ligda:

You neednot call me Miss Griswold unless you prefer . . . I am curious whatinduced you to sit in that windy place for two whole hours . . . canit be that you were looking at the wild onions? I saw so many of themon my trip up here, and each one reminded me of you . . .

I am debatingvery seriously whether I shall come back to college . . . if I giveup college, I hardly suppose that I shall come back to Oakland . .. or see my college friends again soon.

Yours(as usual?) Edith Griswold

***

6/10/04- Dear Mr. Ligda,

I am havingquite a struggle to decide what I am going to do next year . . . Ihave a letter from Mama urging me by no means to give up college.I am glad that you have made the discovery that girls are somethingbeside playthings. But – actions speak louder than words, and – threeon the string, sounds rather like jumping jacks or some other plaything,now doesn’t it?

Sincerelyyours, Edith Griswold

***

6/19/04- Dear Miss …. Griswold:

I am veryglad your mother forces you, an unwilling victim, to return to school.I will have some fun drumming more math into that dull head of yours. . . The only work I like to see a girl do is housework. Then sheappears more womanly to me. I think that women, having proved conclusivelythat they can work, should return to their old occupation of mothersand adored and petted inferiors rather than to be disliked and despisedcompetitors of men . . . About the three girls that I have on a string. . . I should really have said on a thread for the connection isso frail that it broke . . .

Your’ssincerely, Paul Ligda

***

6/29/04- Dear Mr. Ligda: –

I feelthat it would be altogether too audacious for a humble Freshie toaddress a “grave and reverend Senior” by his first name.I think I’ll accept your offer to coach me . . . next term. Iam not coming down till the fall term opens.

Yoursas usual, Edith

***

7/4/04- Dear Edith:

I havebeen waiting for an answer to my last letter. I had been imagininga lot of things. Maybe you were dead or sick or some of the nice lieutshad proved irresistible, or else you had made up your mind not toreturn . . . I was already making overtures to my three girls witha view of making up . . . This is positively the last time that Iwill accept a letter headed “Mr. Ligda”. I shall first lookat the heading of your next letter, and if it is not properly headedwill not read the rest . . . You wonder how I pass the time away?I am testing machines at the University. This and my quartet workkeeps me pretty busy . . .

your’ssincerely, Paul Ligda

***

undated- Dear Mr. Ligda,

I am sorryyou are not going to read this letter, because it is going to be veryinteresting . . . If one of the first lieutenants “proved irresistible”I would write and tell you . . Now will you be good? Don’t delaymaking your choice of “the three” on my account. I am nota candidate for the honor – as long as there are three on your string,anyway!

Goodbye,E.

***

8/4/04- Dear Mr. Ligda,

Shallbe glad to get back to California . . . I leave here on the 13th,leave Portland by steamer Costa Rica at 8 pm Sunday, and reach SanFrancisco some time on the 16th . . . If I don’t see you on 33rdStreet (I want to see you on the 16th or 17th about my study list)perhaps you cold come out to the University.

Sincerelyyours, Edith Griswold

***

Edith did not return to the house next door to the Ligdas, but found quarters at 2226 Chapel Street in Berkeley. Paul resumed his meetings with her. Edith made notes of their get togethers from August of 1904 until January 17, 1905 when she wrote: “Farewell, and if forever ——–!” The entry was probably prompted by news from Paul that he would be moving to San Rafael to run a shop as a civil engineer. He later took a job as Manager of the Smithson Development Company, 438 Crossley Building, 315 California Street, San Francisco. He installed their manufacturing plant and ran it until the company went out of business. 5

Paul’s move indicates he did not then feel his relationship with Edith was serious enough to require that he stay in Oakland. In May, 1905, when the school year ended, Edith returned to her family in Worthington, Ohio, and, later in the summer visited relatives in Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas. Paul wrote on May 12:

“I hope that you have arrived safe and sound in Ohio, that you have been received with open arms by your family that they have killed a fat calf in honor of your arrival, etc., etc., ———– and that at last that you have forgotten your big tormentor, who wishes you a long and joyous summer season and forgetting of the past.”

Edith replied on May 30:

“Oh, how I long for California and freedom! I have slipped back into my old, almost forgotten, saintlike character. I part my hair smoothly, I mind “Mama”, I go to church and teach in the Sunday School. I use no slang, and I do not flirt.”

Paul wrote, while traveling on business, on July 25:

“You go away for months at a time and leave me alone to my temptations. Bessie nearly had me to the proposing point . . . I am going home to supper and then will meet another of my flames. If she catches me in a dark corner it will be all up. Don’t you pity me. I have made love to so many girls, and been on intimate terms with them. Doesn’t this sound conceited?”

Yoursunfaithfully, Paul

At this time, Paul and his three brothers were in the process of incorporating California Engineers Supply Company, a family business which produced a broiler compound. The company was headquartered at 315 California Street in San Francisco (same building as Smithson Development Company), with it’s works in San Rafael. Paul’s business cards show his title as Superintendent of Laboratory and Works. He probably worked in San Rafael. He wrote Edith from there as early as October 4, 1905 into June of 1906 when Edith returned to California to begin her junior year. She lived at the Hathotli Club, 2245 Piedmont Avenue, Berkeley. Paul saw her as frequently as his work and her studies permitted.

Paul left no account of the great earthquake and fire of April 18, 1906. He was issued a pass into the city: “to provide for family.” As he had no family living in San Francisco, presumably he needed the pass to salvage whatever business records or supplies were at the California Street address. If the Company suffered as a result of the disaster, Paul did not mention it in his correspondence.

At the close of the 1905-06 school year, Edith left California for Ft. Leavenworth to spend the summer with relatives. Paul continued working with his brothers to turn the mildly profitable business into one which could support them all. There was considerable tension. Victor, apparently with some ill feeling toward Paul, quit to take a teaching position in Arizona. Even without Victor’s salary, profits did not support the remaining three. Paul decided to turn the business over to Alec and Pete in the hope that they could increase sales to the point profits would support them all. He retained 3,500 of the 21,000 shares in the enterprise and left to accept a job offer from Dr. Hillegass, his sister Valentine’s fiancee. On May 9, he wrote Edith:

“I accepted a job as Superintendent of a mine near Las Vegas, Nevada and will be there in three weeks or so . . . I am working day and night to finish my work here and to break in my brother, who is to take my place . . . It will be awful lonesome so you better sharpen your pen . . .”

Correspondence between Paul and his brother, Pete, reflects a continued optimism that business would increase to the point that Paul could return and resume his position within the buisness. For example, on September 4, 1906, he wrote:

“My brother Alec is working in my place at San Rafael . . . The little business which took so much of my time and care for a couple of years; which nearly died once or twice; which is now a strong and sturdy little affair even well rated in Dunn & Bradstreet, other hands and brains run it. True I am still the President and General Manager but I take no part in its management. It makes me feel sad.

“However my job is still waiting for me. My brother writes that “very soon we will be making enough money to support you with a good salary.” The trouble, which they understand very well, is that they lack an executive man. No business can last very long without one. The rest of the Company is composed of people accustomed to receive orders and directions and not to give them. However they did well in my absence . . . If we keep up at that rate . . . I will be soon wealthy.”

Paul described the place he was working as:“a camp about 9 miles east of town at the foot of a small range of hills. It consists of one 2 room wooden building, three tents, and a stable. The room is the kitchen, the other combination office, parlor, sleeping room, etc.” His working day stretched from 4 a.m. to 9 p.m. with breaks to escape the heat which Paul described as: “something terrible – 120 degrees is not uncommon . . . It was still 100 degrees at 11 last night.”

For the next six months, Paul and Edith wrote each other – a correspondence leading to his proposal, her acceptance, and their marriage. 6 This story unfolds:

***

5/18/06- Dear Edith:

”. . . I will always treasure in a more or less dusty corner of mymemory a recollection of a nice little girl. She did not know theways of the world and had been brought up in a rather puritanicalway, but nevertheless was a very agreeable companion . . . A girlmore experienced in the wicked ways of the world would know that afellow can obtain all the amusement he wants for about a tenth ofthe trouble that I had with you . . . But the fact that I am writingto you now, when I never expect to see you again, shows clearly thatit was not amusement alone that made me seek your company. You sayyou are going to settle in the backwoods of Ohio . . . Is it a palace,a hut, or only a school house? You have also forgotten to tell methe truth about that ring you sported, and which was such a cold blanketfor me . . .”

Yourssincerely, Paul Ligda

***

5/30/06- Dear Paul,

”. . . I always try to speak the truth and so my lies are generallyfalse impressions, things I’ve made you believe without actuallysaying them. I never out and out told you I was engaged. I merelyrefused to say where I got my ring. I was not engaged when I returnedto California last fall nor am I now . . . As for my purpose in tellingthese fibs, you will have to decide for yourself whether I had anyother than pure deviltry and if I did, what it was . . . In spiteof the childlike ignorance with which you credit me, I was never greedenough to suppose you were the kind of man to have only one girl ona string, and sureness of this fact is what prevented my falling inlove with you. Not being in love with you, I was not jealous of you. . . what is my impression of you? It varies, but just now I woulddescribe you to my most intimate friend something like this:

“PaulLigda is a tall, splendidly built man and very strong. His face hasa great deal of character some of which is good and some isn’t.He wears one of those horrid stubby little mustaches but looks a lotbetter without it. If he had come to America while he was very younghe might have learned to be more chivalrous but as it is he has lotsof odious foreign ideas about women, and he’ll never make a goodAmerican husband unless he gets rid of them. He is a “man ofthe world” and therefore more to be trusted in some ways thana young and inexperienced kidling. I’d hate to marry a boy inhis early twenties and have to watch him sow his wild oats. I preferhim later, say at thirty fire or forty – since men are all alike andall sow wild oats sooner or later, so Paul informs me!

“Ido like Paul – I like him very much. I think it’s because heis so much of a man. Women are prone to forgive much – perhaps toomuch – in a man if he is strong and manly and strong in character. . . And so I have forgiven Paul much that I could not forgive inanother, and still prize his friendship, although I have had senseenough not to fall in love with him – much as I have wanted to sometimes,and easily as I could have done so.

“Andthe queerest part of it all is that I do not know whether he evercared for me. He made love to me, it is true, but almost any man willflirt with almost any girl – so that proves nothing. He was too thorougha man of the world to commit himself – and yet, if a man really caresfor a girl why should he hesitate to say so? If he thought that Imight take advantage of the fact that he had so committed himself,why then, he thought me vulgar he failed to appreciate quality, andthat is unforgivable.

“Whenall is said – he was a good comrade and playfellow, he was more -a good friend, but for the rest I can only say “Oh, I don’tknow, I can’t tell!” How I wish I could!

“Thereare lots of other things I might say of you – music, talents, ambitions,ability to order a good dinner, economy, lack of truthfulness, conceit,tender feelings, uncomplimentouness, etcetera, but really I have writtenyou too long a letter already. I am quite sure that you would neverspend so much time and thought on a description of me. Hereafter Iam going to write you no longer letters than you write to me. I amsorry if I have said anything to hurt your feelings again. But youmust remember that . . . you are at liberty to refute any statementI have made.”

Yoursas ever, E. G.

***

6/12/06- Dear Edith:

“Ishould have said “truthfully” “I only flirting withyou. I could not marry you if I would and would not if I could”or else “I love you but cannot marry you” I couldn’tdo the first because 1) it was not true 2) it may be truthful to sayit, but utterly impossible for a gentleman to say even to the lowestgirl, let alone, a lady. I could not do the second because it wouldhave been a direct insult, unless accompanied by expressions of futureand possible disintanglements.

“HoweverI lost your respect on that point. The one cheering thought is thatI could have lost it still more (if possible) if I had proposed, amusedmyself under false pretenses for a while, then “shaken you”,that is if you had accepted me. (If I am getting old my conceit couldnot prevent me from seeing a possible refusal). But the trouble isthat I am a “non-chivalrous” man with “odious Europeanideas about women”. If I had been an American bred, I would probablyhave followed the above plan, which is very popular here. Now willyou be good? In my long and checkered career, I learned one greatlaw: If you “folly” a woman you can do anything you wantwith her, principles or no principles. That is you can win a womanby soft words, compliments etc. Did I ever try to do it in your case?I will confess that I did in “a few” other cases. Some othertime I will speak more fully on my motives for not doing so.”

Yours,P-

***

6/19/06- Ma chere Edith: –

“Atlast I have time to answer your letter in the way you want it —a mile long . . . Let us examine . . . your “description”of me.

“Aboutthe only thing that I find is this. Paul has horrid European ideasabout women —- is not chivalrous and will never make a good Americanhusband.

“Itake off my coat, pick up my shirt sleeves, spit in my hands and takea better hold of my big sword, I mean my fountain pen, which is mightierthan a sword anyhow. I have to deliver a few blows to a few more ofyour prejudices.

“Thetrouble with you is that you have been raised in certain conditionsof life, surrounded by certain class of people, and have formed ideas,not from reflection founded on observation and reading, but by suggestionfrom your surroundings and friends. As some of those ideas are toyour advantage you are still more loath to get rid of them.

“Oneof them is this. A man should be chivalrous to a woman. American menare, European are not.

“Whatis the definition of chivalrous? The way most girls understand itis that a man should obey every whim of a girl and get nothing butthanks and smiles for it; sometimes. He should treat them very politely,never speak evil of them, pay them delicate compliments, etc…. Howdoes it work in practice. Your American chivalrous man does act likethis to one girl at the time and that only before marriage. I wantyou to notice that a high bred man does not in general take off hishat to his chamber-maid, nor compliment his waitress, nor executeevery order of his stenographer, nor help a drunken old woman in distress.No his supply of chivalry is not sufficient for all womankind it isreserved to a few young and pretty girls, and only to those from whomhe expects something. What is the use of having this kind of chivalry?

“Wouldyou swear that every, or even a majority of the American married mentreat their wives in the same chivalrous way as before marriage?

“Iwant to whisper a little secret. It is a well known fact among menthat the only way to get anything out of a woman is by jollying heralong. So your “chivalrous” man pretends that he considersyou an exalted being, superior in every way to himself and – to others.That is very agreeable bait and the American girl raises readily toit. But when she gets old, loses her beauty, etc., unless she is rich,who pays any attention to her? If you want to knock the ideas thatsome of your men friends are chivalrous, just watch how they comportthemselves toward middle aged, or old women that have nothing. Besideswhy should we men be chivalrous, full of respect, and hence considerwomen our superior. Because their face is pretty?. But little girlsare still prettier. Because they are superior mentally? You know thatthey are not. because they are weaker physically? That would createkindness and not respect and admiration. Why then?

“Thewhole thing is founded on the law of supply and demand. Years agowomen were scarce in this country and hence their value was increasedin the eyes of men. They are still scarce in the rural districts andhence are better treated than in the cities where they exceed themen in number. That’s all the poetical origin of chivalry.

“Nowa few words on my position and my “odious” European ideas.I do not consider women my superior in any respect hence see no reasonfor treating them as such. Nor do I consider them as my inferior,and think of them only with contempt, or the idea that they are onlythe plaything of man. I consider them as my equal, and treat themas such. You know by experience that I can be a pretty good comrade,chum, speaking to a girl as I would to a man. My actions towards herare naturally influenced by the difference in sex, but that does notaffect my thoughts. Some girls, accustomed to be treated “chivalrously”think that I am a boor. Those are not bothered very long by my friendship.Some are sensible enough to realize the position that they reallyoccupy in society and take me for what I am worth. To my friend, mychum only will I pay such delicate attentions and compliments, thatwill cause her to feel contented. But she understands all the timethat I do it for her sake and not because I consider her my superior.

“Hopingto soon receive your views . . . I remain

Yourssincerely – Paul

***

6/24/06- My dear Paul: –

“Ihave received and enjoyed two letters from you . . . I am going toanswer promptly so as to keep you amused out there in the desert.I do hope you won’t be too lonely. Lonesomeness is a horriblesensation and one that I have experienced painfully often. SometimesI feel millions of years old, Paul. The terrible experiences I havegone through within the past year no one wholly knows. What I havetold you were the smallest parts. The most I have had to fight outalone and even now I cannot see the outcome of it all. So you mustnot blame me always when I seem pessimistic and disagreeable. I supposeI am only loading your broad shoulders with the blame I may not expressfor the real object of my vituperation – to express it strongly!

“Ireally like you quite well, would like you better if you would onlybe more honest with me. When I spoke of chivalry I did not mean convention.You should be the last to accuse me of attention to meaningless conventionality.I meant what you speak of, the kindness and tenderness shown to aweaker and mare fallible sex. I have heard it said that a Frenchman’spoliteness consists in lifting his hat to the lady he has just crowdedoff the sidewalk when she steps back out of the gutter. It is truethat he American gentleman does not tip his hat to his chamber-maid,but neither does he crowd her off the sidewalk. See what I mean? Notthat I mean to say that you are capable of such a thing as that, butthat you are indulging in sophistry when you say you spared me insultin not declaring your intentions. It is an insult to carry one’sattentions beyond a certain point without declaring one’s intentionof marrying. I am not a fool – altogether -, Paul, and there are certainscenes that stick in my memory in spite of my wish to forget them.Do you think I did not understand? That is why I say that I have forgivenyou more than I could have forgiven most men, because I appreciateyour different standard. I could never have forgiven an American -as I have proved, twice. And yet you call me narrow and prejudiced!I can but smile.

“Don’tyou think we’d better let this discussion drop? I’m so afraidit will degenerate into a quarrel, and I want to be friends. I likeyou, as I have remarked before. Defend yourself against the aboveassertions if you want to, then retaliate by attacking me. I promisenot to lose my temper – unless you call me prejudiced again!

“Whatsort of place is your Las Vegas? What kind of mine is it you are superintending,and how many beautiful senoritas are there in the place? I confessthat I am curious to know how you get along in solitude. Do be good,and let me know how much company you have. You are still such an enigmato me in some ways, that I cannot be quite sure just what you woulddo under such circumstances.”

Yoursas ever, Edith

***

7/3/06- Dear Edith: –

“Youask questions that would take 100 pages to answer, so I will try tocondense.

“LasVegas . . . is a brand new town of 1,000 or so. Half the people livein tents, but we boast of 4 story houses. The native (?) pass theirtime in drinking, chewing and telling lies about their mines, whichare all enormously rich, but which do not seem to prevent them fromtrying to extract money from the tenderfoot. The Senoritas are conspicuousby their absence, the only girls I have seen were Indians. I haven’tspoken to a woman since I arrived. Now will you be good?

“Youwould not recognize me if you met me. My herculean arms bare to theshoulder khaki pants laced boots and a high straw hat are what I wear.My mustache is growing again and quite often a week’s beard.My face and hands are of the color of brick and my weight is downto 187 from 205 three months ago. I feel very strong and healthy though,far better than I did in the city.

“Iheard from two entirely different sources that My Heart’s Desire(?) was keeping company with another man and had publicly announcedthat she was tired of me and it is even rumored that she is engaged.Of course my heart is broken but my appetite is still good so I havehopes of getting over it. If you are interested in my romance I willkeep you posted on further development of the same.

“Myposition in this dreary world is steadily improving. If I keep onI will be able to get married in a year or so. I will send circularswhen I am ready. Shall I send you one?”

Yourssincerely, Paul

***

7/6/06- Ma chere Edith: –

“Ilive with a crowd of Frenchmen and hardly speak any English. Wouldn’tit be fine practice for you if you were here?

“Thislast thought made me stop writing for a few minutes and muse overthe situation. The following is the general trend of my thoughts:My lot here is hard and I am deprived almost entirely of what peoplecall luxuries and lack quite a few necessities. Suppose that I shouldwork that way for a while, save some money and get married. Wouldit be right for a girl to expect to share my hard earned savings whenshe did not share in the work? I do not mean that she has to do asimilar amount of work, but that a wife should have had her shareof the burden, and not simply come in when all the work is done, asmost American girls do. You speak of chivalry to a weaker sex, butdo you think that it is right for a man to bear the brunt of the work,than lay it at the feet of his lady love? Does she realize what itcost him? No in 99 cases out of 100. She only sees a certain numberof dollars which is perhaps not so great as she sees in the possessionof some of her friends, hence they mean nothing to her. She shouldhave helped in the earning not by her own similar work necessarilybut by her presence, advice, sympathy and encouragement. Don’tyou think so?

“Wespoke quite often and I am ashamed to confess that I could hardlyrepeat the subject of most our talks, but one of your sentences stickslike glue to my memory; it struck so hard. “I have been poorall my life and a few years more don’t make any difference.”This was when we spoke on a similar subject. Very few girls wouldsay that and to tell the truth I have set it as a standard. I willnever marry a girl who will not be willing to help me out in my struggles.This is one of the reasons why I stopped caring for Miss H. She wantedto marry someone with money, that is she was too lazy to do her share.I hope she gets what she was looking for. I haven’t heard fromher yet . . . so my hopes are getting strong of not hearing from heragain. Should I write to her? I would like your advice on the subject.

“Hopingthat you are still in good health and that everything is O.K. withyou, I remain”

Yourssincerely, Paul Ligda

***

7/10/06- My dear Paul: –

“Yoursof the 3rd duly received and noted . . . a satisfactory account .. . and interesting. I am sorry there are so many discomforts andyet for some inexplicable reason I like to think that you are undergoingthem. I suppose it is that I like to think of you as a strong man,doing a strong man’s work and “roughing it.” I canimagine that you use a lot of swear words nowadays. Do you? Now thatmy mind is for the present relieved as far as the senoritas are concerned,I must ask if you also join in the whiskey drinking and card playing?Not that I object to your amusing yourself as you please, I merelyask for information.

“Itmust be a very nice feeling to be getting as rich as you are . . .and I shall be very glad to see your circulars when you get them outa year from now. Not, of course you understand, with any idea of applyingfor the situation! Since you told me so frankly of how I missed mychance of catching you, I have felt too “squelched” to dareto think of such a thing any longer. But as I am still fraternallyinterested in you, I should like to see the circular, and trust Imay be honored with your confidence when the happy lady is selected.Of course after that I shall have to stop writing to you, for thoughthe lady would, I am sure, not dare to object to any of her lord andmaster’s pastimes, you yourself will be too absorbed in yournew “playmate(!)” to remember the old one. At any rate,I am glad to hear that “Heart’s Desire” has gone, oris going, back on you. I never did like that girl. “Bessie”is much more to my taste. Well, be sure to let me know how she decidesit.. Well, I must stop.”

Writesoon, Edith

***

7/19/06- Edith dear: –

“Yoursof the 10th received and contents digested. I am sorry that you showthe depth of your depravation in enjoying my misery and discomforts.“Roughing it” sounds very nicely and has kind of an attractiveview in dreams and from a distance . . . but long continued and withouthope of a near relief it is rather disagreeable.

“Inote your question as to my swearing. I am very sorry to disappointyou in that particular point. I don’t swear, not because I wouldnot like to but because the miners here are all French, and hardlyspeak English. Unfortunately my French education was neglected onthe swearing chapter, hence I am deprived of the pleasure of ventilatingmy opinion in good, full mouthed oaths. Only one more discomfort addedto the list!

“Iam also sorry to disappoint you on another point: my favorite pastime.I don’t drink whiskey, as this nectar is not allowed in camp,and I would not drink it if it were as I never liked it anyhow. Asto playing cards, why, I haven’t seen one since I arrived, hencehaven’t played. I live a model life absolutely . . . I wish youto understand however that my goodness is entirely involuntary; Isimply can’t help behaving.

“Butjust the same I have plans for the future. When I am through withthis job I am going to take a goodly part of my enforced savings,and paint the town (S. F. or Los Angeles) the proper kind of a color.I hope you will be around just then. We can have a nice time.

“Butenough on this. You forget to mention . . . what your plans for thefuture are. You are not acting fairly with me. You ask what mine areand don’t tell yours. Why you don’t even tell me of yourlove affairs! This has to stop or else I will write only about theweather or the earthquake, two inexhaustible subjects.

“Heart’sDesire has written at last. I treasure the letter at present, seekingall I can find in it to answer in that unusual caustic style of mine.she won’t forget my answer which is still cooking. In short herletter runs as follows. She found or met a fellow who touched herheart as I never did (probably wealthier is the proper translation)passed sleepless nights worrying about my future without her, thenmade up her mind to shake me. Isn’t that nice? The only nicething in her missive is the part in which she announces that she won’twrite to me anymore and asks for her letters. I am heart broken andam losing flesh rapidly my waist being down to the sylph-like measureof 33 inches! I do not believe that I will ever recover . . . If youdo not answer very promptly your letter will only find a corpse.

“Hopingthe above is satisfactory I remain as usual . . .”

Yourssincerely, Paul Ligda

***

7/22/06- Dear Paul: –

“Yourletter is hard to answer . . . at first it sounds as though it weregoing to be a real sure enough proposal, but alas, I turn the pageand find that it is merely a philosophical discussion of whether awoman is in duty bound to marry a man while he is still poor. I recovermy breath after the comedown, reread to see if you want my view ofthe subject, conclude that you do even if you don’t say so, andbegin:

“No,I do not think it is her duty to help bear the brunt of the struggle.It is instead her privilege, and should be her pleasure. Why, that’sall life is for, to struggle, and when one has won out, or given upin despair, the zest of living is over, and that isn’t the timefor joining hands and standing together. If I loved a man I shouldnot thank him for waiting till he felt able to marry before he toldme that he loved me. A woman’s part, keeping still till she isasked, is pretty hard anyway, and that makes it harder.

“Ibelieve you asked my advice as to writing to Miss H. I suppose youhave forgotten what I told you once – that I thought a man who wasengaged to a girl he didn’t care for ought to tell her so andthen stand for the consequences. Why don’t you write and askher to marry you immediately? Then if she won’t you will havean excellent reason for breaking the engagement altogether. If shewill, that will prove that she isn’t a mercenary wretch afterall, and you can acknowledge your mistake to yourself and take her.And if you’ll take my advice, in the future you won’t mixwith the kind of people who descend to sue for breach of promise.I class them with trash myself, and hope that you misjudge Miss H.

“Ican’t keep my eyes open a minute longer. Try to answer, thisa little sooner, please.”

Edith

***

7/27/06- My dear Paul: –

“Whichlove affair of mine do you want to know about? I should hate to tellyou anything you would fail to appreciate. You will have to ask somedefinite questions and then I’ll tell you what you want to know,if I happen to want to.

“Shallbe very glad to help you paint S. F. red if I am only there. You donot suspect how efficient I can be at that sort of thing.”

***

7/28/06- Dear Edith –

“Yoursof the 22nd received yesterday . . . On rereading your letter I don’tsee anything to answer as you put up no questions.”

Yourssincerely, Paul Ligda

***

8/10/06- Dear Paul: –

”. . . it is simply awful here [Worthington, Ohio] and I feel as thoughI were fifty thousand miles from a friend. You must write to me justas often as you possibly can if my happiness is of the slightest momentto you. Because unless you or someone else keeps me in touch with“God’s Country” which is the West, I shall die of homesickness.There!

“Nowabout your letter . . . I think a man has no business burdening himselfwith a wife if he is going to have to trust to good luck to supporther – and the babies. But if he has a business or profession whichin the ordinary course of events should enable him to support them,if he isn’t burdened with debts or with others dependent on him,and if he knows the right girl – why he ought to marry her ever ifshe will have to do her own housework, and wear clothes when theyare out of fashion. If she is the right girl she will say yea.

“Mycuriosity is aroused, Paul. Who is the girl who started this discussion?There must be some one who is setting you to thinking. You told memy case was settled, and of course it wasn’t Miss H., so it mustbe “Bessie.” Unless you concealed the truth from me, whichisn’t likely. You were always perfectly frank about your “othergirls” which was nice of you. So it must be Bessie. Well, ifyou are convinced that she is the right girl, and your obligationsto your home people aren’t taxing all your resources, go aheadand ask her, and here’s a wish for good luck from

Yoursas usual, Edith

P.S. Ofcourse I don’t mean that really. If you went and engaged yourselfto Bessie I should have to quit corresponding with you, and that wouldn’tbe nice.”

***

8/13/06- Dear Edith: –

“Whichof your love affairs do I want you to tell me about? Why the firstone you were interested in yourself. The ones in which the man onlywas interested have no bearing on the subject and cannot be properlydescribed by you. Now turn her loose.

“Isuppose . . . gentlemen callers have to see you in the refrigeratingpresence of your sister and mother. I don’t think I will go therefor a while . . . I am getting a little homesick or rather, tiredof this pesky place. I know absolutely nothing of what happened inthe world during the last two months. Without joking Chicago may beutterly destroyed, there may be a war somewhere and I would have absolutelyno chance of hearing about it. I receive no paper and the ignorantFrenchmen here don’t receive any letters containing general information.You and brother Pete are my only steady correspondents. My sweetheartshave basically deserted my banner, so I have the feeling of Robinsonin his island.

“Ihave been looking over my old letters reading them over and livingmy old life over. Do you ever do that? Without any intention of flatteringyou, I must grudgingly admit that yours are about the most interestingand contain the largest percentage of thought per words and the smallestpercentage of platitudes. Some of them I intend to keep as long asI live and read the proper extracts for the edification of my children.

“Hopingthat your heart is still warm for the lonesome orphan in the Desert,I remain yours . . .

Sincerely,Paul Ligda

***

8/16/06- Poor homesick girl: –

“Howcan a person . . . be homesick at Home? Hence I stop pitying you onthe spot. Again you say that you will die if I or some one else doesn’tkeep you up with “God’s Country.” Thanks. I hardlythink that you would call this place God’s Country . . . to seeevery day only a few ignorant Frenchmen, with whom conversation isutterly impossible . . . once a week to “town” where I meetonly a few merchants anxious for my money . . . Now be good and don’tcomplain of your hard lot.

“Inotice that your curiosity is aroused about my thoughts of “assuredliving” etc. Your wonder if it is Bessie. I will describe Bessie,then you can form your own opinion. She is middle sized, rather slender,graceful in her movements . . . She is an “undecided blonde”. . . Beautiful eyes with a very kind expression. Now for the mentalpart. High school education which shows only in her perfect spelling.Very few thoughts, and absolutely no original ones. Letters and conversationmostly composed of small talk with the usual hyperbolas: “awfulnice,” “grand time,” “just simply lovely,”etc. I can stand the conversation, owing to her personality, but canhardly read the letters. Serious conversation makes her yawn (figuratively)or frightens her. Considers her education perfect and has no ambitionto learn any more. Reads newspapers and novels. Has a cunning drawlin her voice, which will degenerate probably into a “nagging”voice. Thinks mostly of “good times” and ought to be insociety. Has numberless admirers but prefers (?) — or seems to preferme . . . Now what do you think of my opinion of Bessie?

“Afterwriting the above, I fell in a “reverie.” Many and diverswere my thoughts. Same old subject: What kind of a wife should I have.I suppose by the time I make up my mind I will be white haired.

“Can’twrite any more if I want to save your life and send this.”

Yoursas usual, Paul

***

8/17/06- Dear Paul: –

“Iam afraid that I have rather bothered you with asking you to writewhen you are so busy, but if you knew how pleased I am whenever Iget one of your letters you would feel in some degree repaid. I shouldbe ashamed to ask any other man I know to write as I ask you, butwe have had so many plain talks that it never occurs to me to standon ceremony with you any more! Anyway, I am not worrying about yourmisunderstanding me now. And it is dreadfully lonesome and homesickishfor me now. The old “Long Table Crowd” as we used to callit, is broken up. They are all married or dead or moved away. AndI feel so changed myself. So it is no wonder that I turn to Californiafor comfort.

“Idon’t think you are wise to let a little antipathy to the desertkeep you from holding such a good position. Surely as the town growsyou will not suffer so many discomforts and inconveniences, and anywayI still harbor a little secret conviction that “roughing it”is good for you. Aren’t you glad that you are thinner?! And enforcedabstinence from the dissipations of San Francisco may yet “reform”you. Remember how I used to urge you to reform, and how you used topromise to do so – and never did?

“Bythe way, Paul dear, didn’t you once charge me with inconsistency?How about these two “quotations from two letters of yours, “nowthat I never expect to see you again, etc.,” and “Besides,never to see Edith again! Forget it,” How do you reconcile thetwo? Or rather since they are declarations of two irreconcilable intentions,which is sincere? But no, let me remain in ignorance. “Whereignorance is bliss, ’tis folly to be wise,” says the poet.

“Thisis enough nonsense for one dose. Good bye.”

Yourssincerely, Edith Griswold

P.S. “Iwant your opinion and advice. I don’t wear that engagement ringany more, but I still have it. Ought I to return it? Let me know promptly.

***

8/21/06- Dear Paul: –

“Iam answering your surprisingly long letter at once because I haveonly one stamp left, and someone may borrow it unless I use it first.This is the last letter I can write you before the middle of Octoberor possibly at all, so make the most of it. You see, I am totallybankrupt, and shall not have any money to buy stamps until I get myfirst month’s salary for teaching, and the schools here do notopen till the middle of September. Of course if I do not get a positionI never can buy any more stamps. However as long as you are in receiptof a good salary, there is nothing to hinder your writing to me, sothat the correspondence need not be totally interrupted!

“Iam going down to Cincinnati Friday to meet a Superintendent of Schoolsand a Board of Education. They want to look at me before they decideto give me a position. Remembering your verdict, “not good lookingand not especially bad looking,” I am not cherishing any greathopes. Oh joy, a thought strikes me! Perhaps they want a plain teacherwho will not (presumably) be frivolous, and who will be sufficientlysevere with the children. There is hope after all.

“Aboutmy love affairs, Paul. I am afraid I can’t write about the onlyone in which I was especially interested, since you limit me to that.I have practically recovered from my infatuation. I ought to, forI had my eyes very effectually opened. But I still feel sore aboutthe way the man acted, and don’t like to talk about it. Whenyou come to “the backwoods” to visit my school I may tellyou. Of course there have been other affairs, but none of them especiallyserious – for me!

“Itold you that I was not engaged, even before you fulfilled the conditionI set for asking me. At the present moment I am heartwhole and fairlyfancy-free. I have no admirers here in the backwoods, and nothingdisturbs the even tenor of my progress toward old maidism. Alas! Itis 2 much.

“Iam sorry you are homesick, but don’t see how I can help you,especially since I must cease writing to you. Unless, indeed you canfind solace in that remark of some great man, I forget his name, whosaid that when he was alone he was never lonely, because he was ingood company.”

Goodbyetill October. Edith

***

8/28/06- Miss Griswold: –

“Iwish to inform you that I am not in the habit of associating myselfwith paupers, especially self acknowledged. That a person could notraise the price of even one postage stamp during the space of twomonths in this wealthy country is incomprehensible to the dullestmind. Out of sheer pity for such an object poverty I send you allthe stamps I have at present. If you are able to return them later,I will have a high opinion of your honesty. If not I will simply classifythis with other innumerable deeds of charity that I have performedin my virtuous life.

“Idon’t see why you are in such a hurry to see me married to Bessieor someone else. I am not engaged nor entangled in any love affairat the present time and rather enjoy the novelty of the thing. I amsure that I won’t get married while I am in the desert as thisis positively no place for a woman, especially without occupation.There is no housework to be done here as I must be around the mineall day, she must either follow me around or see me only for a fewminutes before going to bed or getting up. Isn’t that nice? Ifshe lived in Las Vegas, she would enjoy my company one hour or soonce a week. It takes a pretty strong love to do either. Any girlwho wants the job can have it. Now here is a chance! Instead of livingpenniless you would have money in your pocket all the time, but nochance to spend it. Would you like that better?

“Ofcourse this state of affairs won’t continue forever. It is onlya matter of a few months more before I will be in clover in “God’sown country.” I am accumulating money at a fearful rate. I amsending $130 to $140 every month to Oakland. Doesn’t that speakwell for me? The balance I blow in working clothes, tobacco and liquor.You can readily perceive that I am intoxicated all the time with beerat 12 1/2 cents a glass or whiskey at $2 per bottle, and undrinkableat that.

“EnclosedI send you some view of the placeandpeople. Please note the hungry look on my face, and how thin I am(180 lbs). The dirt and oil caked on my trousers can’t be seenvery clearly on the photograph, but with a little imagination youcan see all the details.

“Nowabout the engagement ring. If you have not returned it at the timewhen the engagement was broken off, and if the man did not ask forit after a few months, I think you should keep it as a souvenir. Ifyou should offer to return it, the man may think that you wish torenew the acquaintance etc. Some girls get engaged and break off justfor the sake of collecting rings, and derive quite a little pleasurebesides.

“Hopingto hear soon of you, I remain,”

Yourshopefully, Paul Ligda

***

9/3/06- Dear Paul: –

“Iam returning as many of the pictures as I can spare. I would liketo have the others, but of course if you want them yourself thereis nothing to be said. Oh, what bliss it would be to be your wife!Stingy!

“Iwill also return the stamps. I will send them on the installment plan.You will find the first installment on the envelope of this letter.The others will follow in due time. When I have written you 11 moreletters my debt to you will be paid and you may send me a receipt.

“Don’tworry about me at present. My people supply me with funds. I onlywrote the way I did because I am economizing. I feel that I oughtto earn my own living and not increase my obligations to the familyany more than I can help. They haven’t any too much ready moneyand have done their share for me, and more too. I haven’t sofar succeeded in getting a position. The Cincinnati people electedsomeone else without waiting to have me come down.

“Thefamily are not especially anxious to have me go to work this winter.They think I am too delicate (!) to teach school and want me to stayhome and wash dishes instead!

“Whatgave you the idea that I would like to see you married to Bessie orsomeone else? I never said so. I have been strictly noncommittal onthe subject. As for marrying you in order to have money in my pocket,no, thank you. Marrying for money is treating yourself – and someoneelse – to a free ticket to the infernal regions. If I ever marry aman it will be because we each like the other better than anyone else.I would like a real genuine case of “love,” the kind youread about, but I realize that the genuine thing is not often foundin real life, so I don’t insist on it. I should tho insist onhis being someone I could respect. I couldn’t respect a man whowasn’t his own boss, and kept himself in pretty good order physically,mentally, and morally. I should want him to be my superior mentallyand my equal socially. Etcetera, etcetera. Every girl has her ideason this subject, and pays not the slightest attention to them whenhe pops the question. I blush for the fallibilities of my sisters.I don’t share the one you mention, a weakness for collectingengagement rings. I do hope I am more honest than that. I merely asked,to see what your ideas on the subject are, and am repaid with a vastdeal of sarcasm.

“Knowthen, my dear Paul, that the diamond ring which adorned my fingerwhen you last saw me is in fact an engagement ring, and also my ring,but not my engagement ring. Can you make head or tail of that incoherenttangle of words? I have often told you what my opinion of flirtingis, and I am happy to say that my conscience is clear on that point.I once let a man fall in love with me because I was too young andgreen to know, till it came to the crucial point, that I did not carefor him enough to marry him, and I have suffered enough remorse forit to keep me from ever doing such a thin again willfully. When aflirtation seems to be getting too serious, I speak right out in meeting,and then what happens after that is not my lookout, as we childrenused to say. All the remnants of my engagement in my possession area few letters, perhaps three, and a copy of my answer to one of them.I intend to burn the lot of them sometime.

“Well,it’s time to go and wash more dishes. Let me hear from you soon.”

Yoursas ever, Edith

***

9/4/06- Freshie dear: –

“Receivedyour breezy letter of the 3rd. After reading it, I could have huggedyou from delight. Oh joy, oh bliss, oh heaven – subject enough fora dozen fat letters . . . withering her under the fire of my sarcasm.Well now I will digest your letter sentence by sentence, no word byword . . .

“Iam sorry that I have been refused on account of my wealth, or ratherthat my wealth was not an attraction. Oh very well I will have totry some other way when I have time. You are certainly consistent,as, in another part of this remarkable missive, you say that you wishto marry socially your equal. At the present state of your financesit means a pauper. Well I will wait until I am broke before proposing.

“Iconsider you one of the brightest girls I have met, otherwise I wouldnot write to you. I also consider you intellectually superior to mostmen, although inferior to me (isn’t that nice? Hence —————draw your own conclusions.

Yourssarcastically, Paul

***

9/11/06- Dear Edith: –

“Onesentence struck me in your last letter, “Genuine love is notoften met in real life, we only find it in books.” I am wonderingwhether you are right or not.

“Iwould say there are two kinds of love, the kind we read about andthe kind that really exists and is not scarce at all. When we readof love in books, we overlook too often the fact that books describein full details the few moments and thoughts when the person in loveindulges in the pastime and the writer slides smoothly over the periodsseparating such moments. That is even the book does not pretend toimply that all the thoughts of the person in love are about the beloved,etc. We form that conclusion very erroneously ourselves and alwaysfeel dissatisfied with the real article which we could find at ourfeet. Then again the book for obvious reasons, hardly ever describesthe material part of love, which is the more important of the two.Poo, Poo, at the books.

“Whenyou say “I wish I had a case of genuine love” you mean:“I wish I could like a person so much that I could give my thoughts,my work, my person, my life to him. And I would do it if he lovedme.” If the loved me means simply if he were ready to do thesame for me as I do for him. Simply an exchange of compliments.

“Nowif you knew a man and he did something for you nice and unselfish,you would feel grateful toward him and would feel like doing the sameto him. Multiply these acts by 1000, cube it and deal of purely physicalattraction. Now comes the critical point. Marry him and remove thephysical attraction by satiety, etc. Does love remain? No!

“Butthis is getting disgraceful. I am writing too much to you lately.”

Yoursscientifically, Paul Ligda

***

Edith could not respond while she was away in Columbus for the Ohio State Fair. She did mail Paul a note on September 9 saying she hadn’t heard from him in a week, but was looking forward to reading his letters when she returned to Worthington the next day. The letter she found waiting was Paul’s of September 4 in which he had written: “here I better stop or I will be proposing to you next. I wonder . . . ” Edith responded indirectly:

9/14/06- Dear Paul: –

“Iam glad to hear that you are intending to be rich some day. In viewof this fact, why do you tantalize me with a suggestion that thereis still hope for me? Didn’t you yourself solemnly assure methat I had lost my chance?

“Supposinghowever that you really want to know what I would say if you proposedto me, I shall answer it seriously. There are several reasons whyI cannot tell you what I would say. Have you ever read “An OldFashioned Girl?” In this book one scene greatly impressed me- The critical moment arrives, and Tom says, “Oh, Polly, do youlove me?” and Polly, dear girl, replies, “Suppose I saidthat I did, Tom, and you should say you were sorry you could not reciprocate.How awkward I should feel!” Suppose I should say, “Yes Pauldear, I shall be very glad to accept you if you will only ask me.”and then you should say, “Well really, I’m awfully sorryfor you, but I haven’t the slightest intention of ever askingyou!” How awkward I should feel

“Mysecond reason for not telling you is that I am not quite sure thatI wouldn’t change my mind when it came to the point of sayingyes or no. I had an experience of that kind once, you remember mytelling you recently.

“Mythird reason for not telling you is that I have already told you severaltimes, not in so many words, it is true, but still in pretty intelligiblelanguage. I shall not tell you any more plainly until you put thequestion plainly. It is up to you. If you really want to know, youknow how to find out!

“Writesoon. I am awaiting that proposal with much eagerness. If ever I getit I will tell you a joke on myself.”

Yoursas before, Edith Griswold

In her note of September 12, Edith had mentioned that her brother, Ted, was to be married. She added, “Interested?”

9/18/06- Dear Edith: –

“Youask if I am interested in Ted’s marriage. Why should I be interestedin any marriage in the Griswold family excepting your own and evenon that one if I were not the victim? I haven’t the honor ofknowing Ted or the family unless Ted is the Oakland brother. Afteryou went away he would not recognize me on the street so I would retaliateby not being interested in his marriage. Boom!

“Nomatter who Ted is he is a lucky fellow. He found a girl who was willingto share his lot. So I envy him. I wish I could find a girl to sharemy present lot. By the way maybe you would be willing. If you are,please tell me, and I will propose in the most exquisite way . . .I know it would captivate your, then you could take the next trainto Las Vegas and I will have the minister – blacksmith – justice ofthe peace ready, then go for a honeymoon in the Desert. Wouldn’tthat be nice?

“Imust say the Desert is not so bad as it was in summer. The days arestill warm but not oppressive. The mornings and evenings are simplydelightful. We are a little more comfortable now than we used to be.I have a big room to myself with a floor, two windows and even a stove.The roof does not leak. I also have a couple of pretty fast horsesto drive to town, ad money at libitum. Now doesn’t all this fascinateyou? Of course, I will throw in as much love as you want, since youinsist on the obsolete article, but this I will reserve for my formalproposal and after marriage.

“Hopingthat I will very soon get an answer, I remain –

Yoursimpatiently, Paul

Paul mailed his indirect proposal on the 18th. The next day he wrote:

“I have no fortune to offer, no brilliant future, but my wife would never want so long as I had strength to move around. She would also be happy so long as she desired and it were in my power to make her. I do not promise to be her slave and obey all her whims, nor do I intend to be her master in all actions and thoughts. I offer a position of equality. All problems arising in our lives would be discussed and the more competent person would take charge of the solution. I shall have indulgence for her foibles and expect her to return the compliment. In short I will honor love and cherish her so long as she deserves it.

“Suchis the future I would offer you Edith . . . I have always liked youvery much – I believe you are just suited to me. You once said thatyou liked me very much and would have liked me more if I had shownyou more respect. I am now giving you the greatest proof of my respectin my power; I ask you to be my wife.”

Paul did not mail his formal proposal, but kept it awaiting a response to his indirect proposal of the 18th. It took about five days for delivery of a letter between Ohio and Nevada. Edith wrote a letter on September 21, the contents of which made it clear she had not yet received the proposal. As he waited, Paul wrote again.

9/22/06 – Dear Edith: –

“Idon’t dare to change the above yet, as I haven’t an answerto my last letter. I really ought to wait for it before writing toyou but decided to write for two reasons. The first is that, if theanswer is favorable, you would not mind getting news from me, if unfavorable,it won’t make any difference . . .

“Sincewriting the last letter life took a new aspect. I am spending my sparetime thinking of the beautiful future, what we would say and do if_____________ It took me a long time to make up my mind to do it chieflyon account of my unsettled finances, but you could see the thoughtstrotting through my head, if you read my letters carefully.

“Buthere another thought comes up . . . If she should refuse!!! What wouldI do then? I have been buffeted so much in this world that I havelearned to always make two plans, one in case of success in my venture,and the other in case of defeat. In the later case I first would tryto resign myself philosophically to my fate and mechanically try todivert my thoughts into other channels. I would leave this positionwhere I have too much time for thinking and would plunge into activelife. Mexico, Panama, or South Africa would probably be honored bymy presence, as I can get a position in either place. My little compoundbusiness can take care of itself by what my brother writes, and thereis too much leisure for me. Would I try to get acquainted with girlsagain? I doubt it, as I would have lost all faith in women. I wouldprobably become a hardened old bachelor. Maybe I would retire fromthe world into a University where mental work, for which I alwayshad a fondness, would prevent me from thinking and remembering.

“WouldI plunge into dissipation not being restrained by any good influence?Hardly. I have sown my wild oats pretty well and harvested the usualcrop. I had so many “good times” that they are not goodany more. Well this letter is turning out pretty gloomy. I think andhope that your answer will be such that I won’t have to indulgeany more in such thoughts. I remain

Yoursexpectantly, Paul Ligda

Before mailing this letter, Paul received Edith’s letters of the 14th and 18th. He responded along with his letter of the 22nd.

9/24/06 – Dear Edith: –

“Receivedyour double letter of the 14th & 18th inst. Must commend you on yourthrifty and saving habits. Said letter is kind of encouraging andmakes me hope for a favorable answer . . .

“NowEdith dear I am surprised that you have such a small opinion of meas to insinuate that I would ever answer “I am sorry but I don’tlove you.” I don’t indulge in such pleasant catches, andif I had been a hypocrite looking merely for amusement at the timeI saw you would have professed my undying love, etc. You would probablyhave been satisfied as women like to believe words of mouth.

“Hopingto hear soon off you, I remain yours

Lovingly,Paul

Edith apparently received Paul’s proposal on September 27. The wording left her still somewhat in doubt. Her response was brief.

9/27/06- Dear Paul: –

“CivilService exam tomorrow and I am too busy to write at length. But sinceyou are waiting “impatiently” for an answer – stupid, astho I hadn’t told you on an average of once a month for say twoyears now – the idea of a honeymoon in the desert appeals to me. Isn’tthat nice?

“Willwrite Saturday more fully,

Yours,Edith

P.S.When it comes, I shall say, “Oh, this is so sudden!”

On September 29, she added: “I have yet to gain the consent of my loving family. I haven’t said anything to them yet . . .”

Edith was, perhaps, still uncertain of her status. On October 1, she wrote:

“It seems as though I must be engaged to you, yet how can I be engaged to a man who doesn’t know I have decided to marry him; and, as a matter of fact, hasn’t even proposed?”

Meanwhile, on October 2, Paul felt certain enough to make a direct commitment to marry Edith:

“I wonder if you will come to Las Vegas and get married. Come to think of it, I have to propose first. Here goes . . .

“Dear, dear Edith . . . will you be my wife?”

On October 10, with Edith’s acceptance virtually assured, Paul mailed the proposal he had written on September 19. In fact, Edith had written on October 8:

“I suppose now that I can consider myself really and truly engaged to you, can’t I? How queer it feels, pleasant, but sort of “shivery, too.”

Paul responded:

“You say that you are happy to have a “shivery” feeling. Over what: I don’t bite. I certainly intend to do the best I can for you and will try to make you happy.”

He was anxious to set the date:

“I think a winter in the desert will do you more good than a winter in Ohio. How soon do you intend to come to Las Vegas? I positively won’t wait over two weeks.”

On October 13, Edith, after checking the fares, found there was an excursion rate until October 31 and asked: “Do you want me that soon?” But she also advised that she had yet to tell her family. When she finally told her mother, her mother said: ” . . it didn’t seem right to her . . . for me to go to Las Vegas . . . permissible, but hardly desirable.” Edith added that she couldn’t ask for money for the trip: ” . . . so if you want me, you’ll have to finance the enterprise. I should much prefer waiting till I earned some money myself. It is rather humiliating to accept your money before I am married.”

Paul jumped at Edith’s offer. On October 20, he wrote:

“So I have to finance the enterprise. So much the better . . . I have absolutely no use for money here . . . I do not want to wait until you earn money yourself . . . I will send you the $65 fare and $10 for a sleeper. Now will you be good and come quick? My conscious is troubling me about an engagement ring, but I can’t do anything here as there are no jewelry stores. Would you consider it humiliating if you had to buy one with money I sent you? The same applies to wedding rings . . . I hope to receive a telegram in a week announcing your arrival.”

As it turned out, the fare was greater and Edith felt November 24 (her 23rd birthday) a better date for the marriage. “That would sort of condense anniversaries in the family and be a nice start on my 24th year.”

Paul was dismayed. On October 29, he chided:

“I have received the sorrowful information that you don’t want to be married until the 24th of November. Four more weeks of single blessedness. All right. I will get a pound of morphine tomorrow and sleep the time away.”

Edith was unable to complete her plans. On November 11, she wrote: “I am beginning to despair of ever getting ready to come.” Then, when she actually had the ticket, her family stepped in.

11/14/06 – Dearest: –

“Iwrote you a few days ago . . . telling when I would start. but I didnot send it, for yesterday the family held a council of war, and -they will not let me go. I have been crying all night and I can hardlysee to write. If you say anything unkind to me it will break my heart.It is cruel to disappoint you so at the last minute. It is cruel tome, too. They might at least have told me in the first place, insteadof waiting till the day before I had planned to start . . . They sayit is my duty to stay home and help Mama. And they put it in sucha way that I cannot refuse. As you know, I am indebted to the familyfor my college education, and I have never done anything especialto help at home, and I am the only one left here . . . So all I cando is to beg your pardon for raising false hopes – remember they weremy hopes too – and to tell you that you are, if you wish, releasedfrom you engagement to me. Oh, Paul.”

Ever yourslovingly, Edith

Luckily Paul didn’t receive this letter until after Edith was able to convince her family to allow the marriage. On November 16, she wired: “Disregard Wednesday letter. Leaving immediately . . .” En route, she stopped to accept the best wishes of relatives in Ft. Leavenworth and in Denver. She did not arrive in Las Vegas until December 4. Paul and Edith were married the same day in the parlor of the Palace Hotel.

Paul liked being married. His work seemed easier. He was involved in digging a tunnel to a ledge where the investors, primarily Dr. Hillegass, believed they would find gold at about 1,240 feet. Progress on the tunnel varied – usually 5 to 7 feet/day. He hoped to strike gold before work would have to be delayed because of the intense summer heat. Edith was pregnant. In May, as the days began getting hotter, they decided it would be better if she stayed with Paul’s mother in Oakland while Paul finished the job. Sharing the home were Pete, her 27 year old brother-in law, and Valentine, her 20 year old sister-in-law. She wrote: “Mrs. Ligda is very good to me. So are the others for that matter. They gave me a set of table silver . . . a deferred wedding present.”

This was to be the first of many separations their marriage would endure. Paul wrote frequently announcing his progress with the drilling. As he neared 1,240 feet, Dr. Hillegass came to the camp to supervise the work, but with temperatures of 130 degrees in the engine room, and with frequent resignations from the crew, the work had to be stopped. After being away from home over a year, Paul returned to Oakland promising Dr. Hillegass he would complete the drilling in the fall.

Paul resumed working in the family business. He and Edith moved to San Rafael to be near the works. Their first son, Victor Worthington, was born there on September 17, 1907. Paul was delighted to be a father. He had the company of his son for the first six weeks before returning to Las Vegas to honor his commitment to Dr. Hillegass. He lamented: “Why is it my fate to be always separated from my friends and from good things?”

Paul was back in Las Vegas on November 2. He noticed the town had changed: “At least 4 new buildings have been erected; half a dozen tents are gone, and a few buildings have been painted. But money seems to be pretty scarce, and everybody wants to do business with me.” The work did not go well. He first expected to reach the ledge in: “3 weeks or so.” They did not. On November 13, he reported: “We are in at 1285 feet. The rock looks the same as ever, and the only gold in sight is what the Doc spends.” The drilling continued to 1,360 feet. Dr. Hillegass decided to go to 1,400 feet. There was still no strike. On December 2, Dr. Hillegass came to the mine. After watching the progress of the drilling and consulting with his surveyor, he felt they would be more likely to find gold by cross cutting. The drilling continued, so Paul and Edith celebrated their first anniversary apart. He wrote it had been a year of happiness:

” . . . I did not think possible. Toward you I have nothing but the best feelings . . . I wish you were here now. I believe that I would tell you all the nice things that lovers are supposed to deliver to their flames . . . I will try . . . you are the nicest little girl I ever knew, and I am mighty glad that you belong to me . . . After a year of your company I would gladly pledge myself again to love, honor and cherish you . . .”

Edith shared his feelings:

“If all the rest of our married life is as happy as this first year has been, I shall be satisfied . . . I am longing to have you home again . . . I miss my best friend more than I do my lover, to have someone to talk to of all the little things that are too intimate to tell an outsider and too trivial to write . . . someone to comfort me when I am tired or lonely, someone to do the dear kind things you used to do for me, someone to be patient with me when I do wrong . . . there isn’t a minute of the day when I am not missing you.”

Cross cutting didn’t result in a strike. On December 10, further efforts were abandoned. Paul was home in San Rafael for Christmas, 1907.

With the mining venture behind, Paul resumed his position as President of the family business. Sales increased as did repeat orders. Profits were adequate to support all three brothers. On September 27, 1909, the Ligda Brothers assigned the rights to the process by which the broiler compound was made to the corporation. The corporation then issued additional stock, much of which was purchased by Dr. Hillegass, who came into a position of control in the business. After the reorganization, there were plans to expand and to move the works out of Marin County where the supply of eucalyptus trees was thinning. The leaves of the tree were an essential ingredient in the production of the compound.

On August 12, 1909, Paul and Edith had their second child, Barbara. With the business doing well, Edith was able to take the children to visit her family in Ohio over the holidays. Paul stayed behind to help in looking for a place to move the company works and to find new housing for his growing family. He first rented a furnished room for $5/week on Clay Street in San Francisco near the company

office in the Santa Marina Building at 112 Market Street. With plenty of idle time, he renewed the acting career he had begun in college. He had a role in “Colly’s Widow,” which played a week at the Alcazar Theatre. He then joined the Alcazar Quartet, which appeared nightly in “Blue Jeans” and in other performances. Paul had a wonderful singing voice and sought opportunities to perform throughout his life. He is mentioned as a soloist in a program at the Central Theatre in San Francisco on December 2, 1910.

Despite the excitement of his theatre appearances, Paul wrote that he “felt lost” in San Francisco. He concentrated his house hunting in Oakland where he felt rental prices were more reasonable, e.g., ” . . . for about $20 we can get a cottage or bungalow of about 4-5 rooms with gas and electricity.” He actually did a little better renting 563 E. 24th Street, a two bedroom cottage with water, gas, and electricity for $18/month. Edith returned from Ohio to their new home in January, 1910.

Paul remained as President of California Manufacturers Supply Company after the reorganization. On November 22, 1911, Pete and Paul put their stock in the new company in a voting trust of 7,200 shares with George E. Bennett who held 2,200 shares. Under terms of the trust, H. P. Jacobson, the trustee had to vote all shares as directed by the majority, i.e., any two of the three shareholders. By this device, the Paul and Pete exercised greater control. Nonetheless, according to family accounts, controlling interest had passed to Dr. Hillegass who was expected to become a member of the family after his marriage to Valentina Ligda to whom he was then engaged.

The marriage did not take place. Val fell in love with Phil Heuer and, despite pleas from others in the family who saw the marriage to Hillegass as providing financial security, married Heuer on January 10, 1912. Dr. Hillegass, crushed by Val’s rejection and perhaps feeling Paul or Pete were in some way responsible, withdrew his support for the business. On January 15, Pete and Paul removed Mr. Jacobson as trustee of their voting trust, but by May 26, the business collapsed. Pete abandoned his family and moved to Southern California where he tried to start another compound business. Paul, nearing his 40th birthday, with a wife and three children (Theodore having been born on January 28, 1912), was out of work. His relationship with his sister, Val, remained strained for years.

Paul looked for work near home as a manager in some form of construction or manufacturing. He was not successful. The early months of 1912 became what he described as a period of “worry and unrest” as family savings dwindled. With few options, he took work as a foreman wherever a job would take him: first to a ranch near Belmont; then back to Las Vegas. He returned to Oakland to escape the summer heat, but still could find no work near home. On August 21, 1912, he again left to take a job with Stone & Webster Construction Company blasting tunnels in the Sierras near Auberry in Fresno County. He wrote:

“Why couldn’t the world be a little more gentle to us? To you specially? . . . I hate to have you stand such sorrows . . . During the night I often thought of you and the kidlets and how nice life has been so far with us. I also thought of how lucky it was that I kept in good condition for hard work. It will always deep us alive . . . until better times and other chances come. I am still full of good intentions and am thinking of more.”

Despite the discouragement of being unable to find a management job near his home and of having to take a job as a laborer in a work crew among 2,000 men working 12 hour shifts over a 6 mile area, Paul was hopeful:

“The more I see the conditions here, the more I realize that there is a good chance here to climb up to a good position. The first thing to do is to give satisfaction to my particular boss. Once this is done and he feels well disposed toward me I will explain to him that I need the money, and he will recommend me to any other boss a a good steady man. repeating the process several times will land me near the top of the pile. There are lots of good jobs here and changes are very frequent . . . I am going to get up again, I must and I will.”

With savings almost exhausted, the Ligda financial situation was serious. Paul sent the bulk of his $3/day wages home with frequent apologies there was not more, but always with assurances:

“I am doing my best for my dear little family now and will continue to fight as long as I live. You know me well enough by this time, and I hope that you are sure that as long as I am able to do so I will work for you and do it with pleasure because I love you all and you my wife better than myself.”

To help, Paul cut his own expenses, e.g., “As soon as I run out of tobacco, I will stop smoking as we cannot afford the 10 cents per day that it costs.” His attempt was unsuccessful, but he did report that he cut down. He also reported: “I have not had a drink since I left . . . and have no desire for one.” He wrote of his frustration of paying $1 for working gloves which would wear out in a few days – a problem he solved by making gloves out of old shoes. Still, he saw the need for some frivolous spending. After selling his meershaum pipe and one of his curves for $2.75, he sent the money to Edith with this instruction:

“I wish that you would use the $2.75 as follows: $2.00 strictly for yourself and 25 cents for each child. It is not money earned hence should be applied to luxuries.”

Paul missed his family deeply:

“I am mighty sorry that I cannot help you except by the money that I earn and my best wishes. You are a great help to me even when you are far away, for whenever anything disagreeable happens . . . I think of you and . . . the thought encourages me to do my best. However I miss you a lot. I also miss the babies. I would like to be present when Victor masters his letters, Barbara learns some new accomplishment, or Teddy begins to crawl . . .”